How does race strategy change for different motorsport championships?

As motorsport has embraced the latest powertrain technologies over the last decade, its regulators have pioneered new racecars, classes and categories of racing. This has led to motorsport featuring the widest range of high-level championships ever. From electric single-seaters to hybrid endurance racers as well as top-fuel dragsters and hydrogen-powered prototypes, there is a race series for everyone.

The strategic challenges of different series

Each of these championships varies either by regulation or race length which means that, depending on the category, race pace can be limited by tyre degradation, fuel saving, battery energy or driver stint times. These differentiators create various ways to get to the end of the race in the fastest possible time; demanding a unique approach to race strategy for each series.

In the highly refined world of Formula 1, cars are very closely matched and depend on maximising tyre performance and life. Whereas, IndyCar has a similar tyre dependency but also introduces the variables of refuelling as well as long and short oval racing and more unpredictable track surfaces.

Endurance series such as WEC and IMSA incorporate a wide range of technical regulations within their different classes. From the top level LMDh/Hypercar/GTP regulations through to LMP2 prototypes and road car-based GTE’s, these series have to contend with driver changes, night racing and stint length regulations on top of tyre changes and refuelling.

To get a feel for the differences between championships, Table 1 summarises the main characteristics of some of motorsport’s major series. All feature races of 90 minutes or longer and all require pitstops. Of course, there are too many variations to summarise them all, circuit to circuit and format to format, even within a championship. For example, the Indy 500 is a very different race to its Indy Road Course equivalent, while the Le Mans 24 Hours is a unique challenge compared to the other events on the WEC calendar.

| Series | Event | Race laps | Race time | Race distance | Expected pitstops | Pit stop time | Time in pits |

| Formula 1 | All | 44-78 | 2hrs | 300km/188mi | 1-2 | 2s | 25s |

| IndyCar | Indy Road Course | 85 | 2hrs | 330km/206mi | 3 | 7s | 40s |

| IndyCar | Indy 500 | 200 | 3hrs | 800km/500mi | 6 | 7s | 35s |

| WEC/ACO | Le Mans | 400 | 24hrs | 5000km/3125mi | 31 | 60s | |

| WEC | Spa 6hrs | 128 | 6hrs | 900km/562mi | 5 | 60s | |

| IMSA | Sebring 12hrs | 320 | 12hrs | 1920km/1200mi | 17 | 60s | |

| British GT | Silverstone 500 | 78 | 3hrs | 456km/285mi | 3 | 135s |

Formula 1

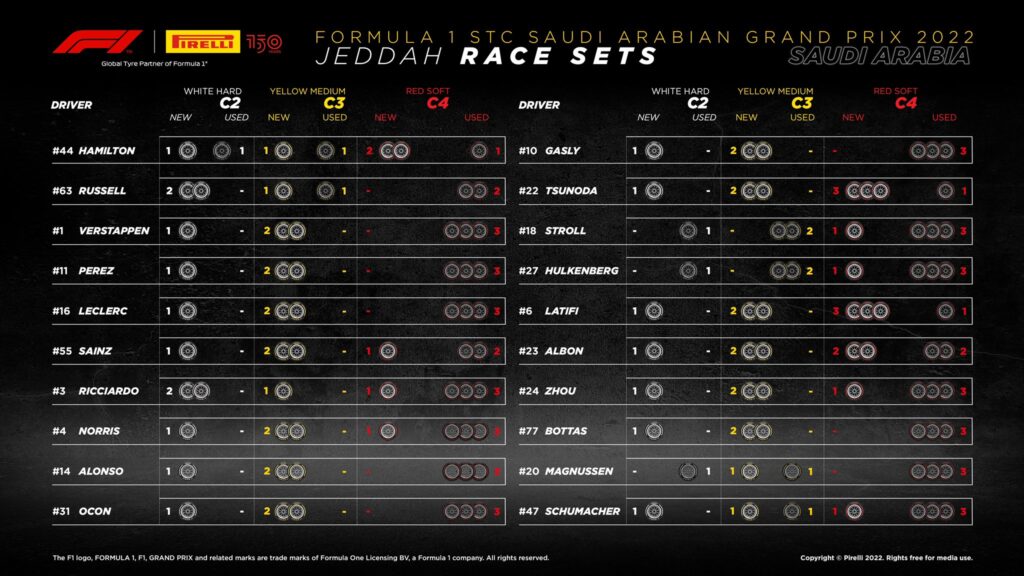

✔ Multiple tyre specifications per event

✔ Tyre set limits per event

✔ Mandatory tyre specification change during race

- Spotters

- Balance of performance

- Refuelling

- Driver Categories

- Minimum pitlane times

- Minimum/maximum driving times

Modern Formula 1 is unique in that it requires teams to design and manufacture their own cars. Whilst this sets relative car performance, an effective race strategy along with good tyre management means it is always possible to beat a notionally faster car.

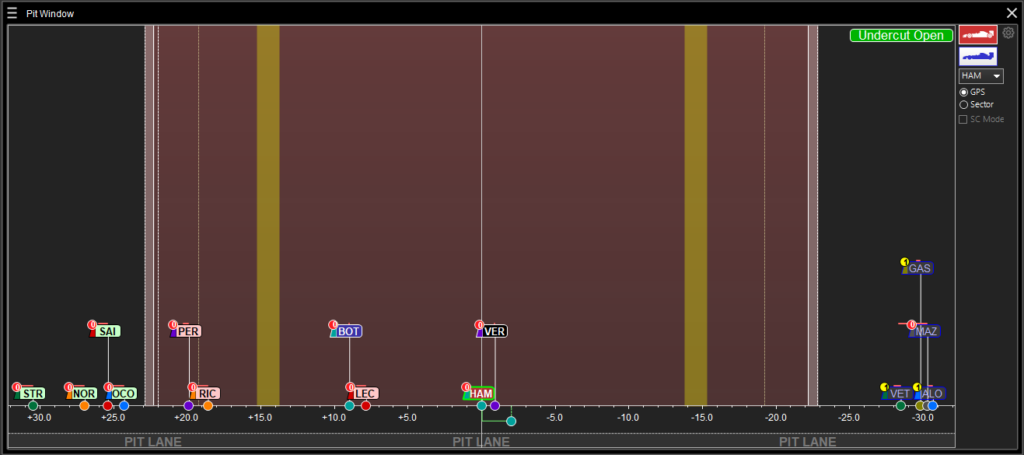

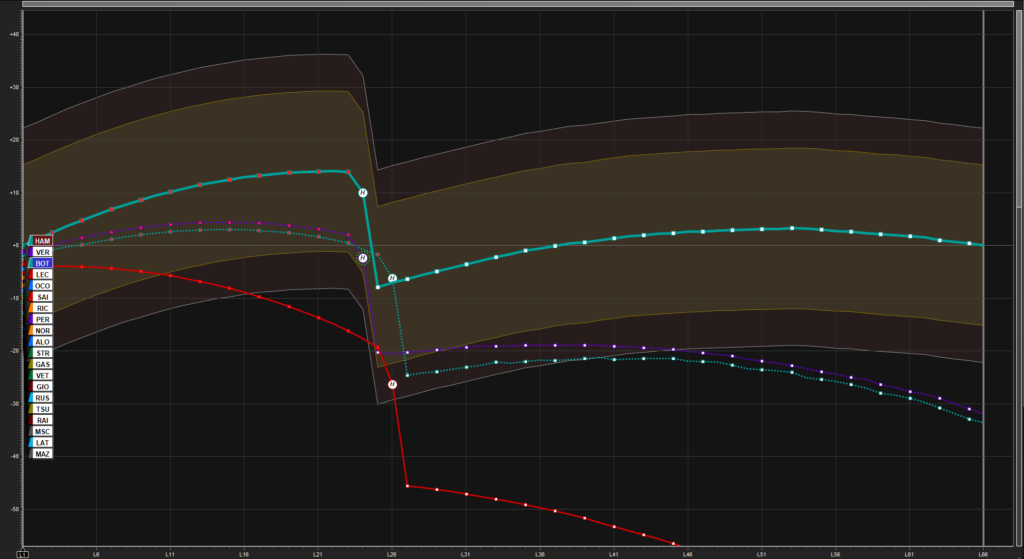

As Formula 1 has no refuelling, stint lengths are defined by either tyre life or by teams seeking a tactical advantage. Undercutting a car in a pitstop by switching onto a faster tyre or overcutting a car by taking advantage of better tyre life and slow warm-up enables cars to pass competitors without overtaking on track.

To monitor the evolution of competitors’ tactics throughout a race, teams turn to strategy software such as RaceWatch. This allows them to track the tyre degradation and race pace of their drivers as well as their rivals in real-time so they can constantly analyse the threat of an undercut or overcut and react accordingly.

The other strategic variables that strategists have to react to are yellow flags and safety cars. In Formula 1, these regulations are relatively straightforward. There is either a dash timer-controlled virtual safety car or a physical safety car on track but in either scenario, the pit lane remains open at all times. This presents an opportunity to pit under a safety car and minimise the time lost during a stop relative to green flag conditions which can help cars jump their competitors, particularly when track position prevents other cars from taking an advantage.

IndyCar

✔ Multiple tyre specifications per event

✔ Tyre set limits per event

✔ Mandatory tyre specification change during race

✔ Refuelling

✔ Spotters

- Balance of performance

- Driver categories

- Minimum pitlane times

- Minimum/maximum driving times

In previous years, IndyCar typically experienced negative or negligible tyre degradation during a race, where the tyres would actually get faster throughout a stint. However, the recent introduction of alternate road and street course tyres means that IndyCar now suffers from the same degradation problems as Formula 1, with grip reducing each lap resulting in slower lap times.

However, a key difference is the lack of tyre blankets in IndyCar which makes a successful undercut strategy unlikely because a new set of tyres takes longer to warm up. The variety of circuit types, surfaces and tyre compounds means that each event produces different strategic requirements. This is further complicated by the ability to refuel during pitstops, as the cars no longer carry enough fuel to complete the race. Consequently, stint lengths can be dictated by fuel capacity and fuel fill levels, and with 10kg of fuel worth 0.2s of lap time, carrying unnecessary fuel comes with a considerable lap time penalty.

The IndyCar yellow flag and safety car rules are also more complicated than Formula 1. The pit lane closes under caution which can result in penalties and time loss if misjudged. On road and street courses, teams tend to pit towards the front of the pit window because if a yellow comes out, drivers must wait until the pitlane opens again by which time the pack has completely bunched up. Whereas on ovals, a pitstop can put a driver two or three laps down, so teams try to stop towards the end of the pit window. This means that once the pack has bunched up, a driver can complete a pitstop and re-join the track on the same lap.

WEC\IMSA

✔ Multiple tyre specifications per event

✔ Tyre set limits per event

✔ Balance of performance

✔ Refuelling

✔ Driver categories

✔ Minimum/maximum driving times

- Mandatory tyre specification change during race

- Spotters

- Minimum pitlane times

Endurance racing perhaps offers the most complicated set of strategic options. The races still include tyre and fuel management, although heavier cars and more conservative tyres often make these less influential on lap time. However, fuel consumption management can be crucial if it means that a stint can be extended to reduce the number of pitstops.

The requirement of multiple drivers in endurance racing adds further complexity to the race strategy. Accommodating three different drivers requires careful management to ensure that the total driving time of each driver is within the regulations. So, as well as managing tyre life and refuelling, strategists must monitor how long the drivers have been in the car. In shorter events, this may be a maximum or minimum total driving time within the race. Whereas a 24-hour race requires the so-called 4-in-6 rule whereby a driver can only drive for four hours in any six-hour window.

With over 35 racers on track, endurance races can have numerous full course yellows, slow-zones and safety cars, with multiple safety cars on track in the case of Le Mans. It can become easy to fall foul of a stint length limit when a lap behind the safety car is much slower than a race lap.

The final element of endurance racing which influences strategy is the Balance of Performance (BoP). To achieve a level playing field across the different car designs, organisers utilise a variety of tools including ballast, boost, refuelling rates and fuel tank capacity to cap performance. Teams will attempt to achieve a good BoP through events and across a season.

GT races

✔ Tyre set limits per event

✔ Balance of performance

✔ Refuelling

✔ Driver categories

✔ Minimum/maximum driving times

✔ Minimum pitlane times

- Multiple tyre specifications per event

- Mandatory tyre specification change during race

- Spotters

Many SRO endurance series run slightly shorter races than WEC or IMSA events but introduce GT3 and GT4 cars with professional and amateur driver combinations. The same driving time limitations exist, but there is now the potential for a much bigger lap time difference between two drivers within the same car. A good amateur may be 2s slower than the pro, offering a strategic advantage of putting the professional in the car, whilst rivals have their amateurs on the track.

These series can also have mandatory stops to enforce strategic variation and minimum pit lane times to prevent rushed driver changes and refuelling. Managing the time in pit lane to only exceed this by a few tenths can result in a pass on track. In longer races, with multiple mandatory stops, strategists will look to safety cars to gain track position and minimise pitstop losses. Often minimum pit lane times will put a car a lap down temporarily, which can become permanent with an unlucky safety car.

Formula E

Formula E requires a completely different strategic approach to other racing categories. This one-make series races on grooved, control tyres that experience minimal degradation during short races with no pitstops. However, these electric racers start with not enough energy in the battery to drive flat out to the finish line, and so rely on recovering energy under braking. This also requires drivers to drive as efficiently as possible; compromising track position if it means saving enough energy to get to the end of the race.

Other features like attack mode must also be considered. Each driver is allocated 8 minutes of attack mode where they receive a 50kW boost, increasing their battery power to 350kW. However, to activate this, drivers have to take a slower line around a corner through an activation zone, often losing places. The timing of taking attack mode is crucial to determining how many positions a driver can lose. Furthermore, attack mode can’t be activated under a safety car, so if a team waits to the end of the race to exploit the extra power for a final push and there is a safety car, they will be penalised for not taking their full allocation of attack mode minutes.

The variety of race series and the performance differentiators within them demand a completely different philosophy for determining the optimum race strategy. However, regardless of the series, strategists need the latest, most relevant information displayed clearly and concisely to inform their decision-making and enable them to react faster to the rapidly changing circumstances of a race.